Free Sources of Management Studies

Those who have read my earlier posts on evidence-based management have learned about “The Management Knowledge/Practice Gap”; discovered one reason for it is that “Good Evidence is Hard to Find”; and become skeptical readers about science because “Studies Say, Question Articles about Studies.” Now comes your chance to close the gap by finding useful studies on your own. You have to invest some time and effort, but that investment will save you time and effort down the road. Other than maybe some gas costs, though, you don’t have to invest money.

Those who have read my earlier posts on evidence-based management have learned about “The Management Knowledge/Practice Gap”; discovered one reason for it is that “Good Evidence is Hard to Find”; and become skeptical readers about science because “Studies Say, Question Articles about Studies.” Now comes your chance to close the gap by finding useful studies on your own. You have to invest some time and effort, but that investment will save you time and effort down the road. Other than maybe some gas costs, though, you don’t have to invest money.

There are at least four ways to read scientific studies for free, but each has plusses and minuses. Three of them—Google Scholar, your local library system, and open-access research databases like SSRN—are free via the Web. However, these cover a small portion of all studies done on a topic. Google Scholar and your library system will mostly provide abstracts or articles about studies, rather than the studies themselves. Full-text journal articles in Scholar tend to be older ones, not the most current information. The research databases have full articles, but many are earlier drafts that may contain errors or have not gone through the peer-review process.

Fortunately, many college libraries provide guest access to large databases that allow you to download or e-mail complete journal articles. You must physically go to the library unless you are a student, staff, or faculty member, and access may be limited to specific computers and/or short lengths of time. But you can easily walk out with dozens of studies relevant to a decision you are trying to make.

At U.S. public universities, I’ve never had a problem getting the same kind of access the students have. Well, that’s not entirely true. One clerk hassled me at a library where I’d had no trouble before, so I complained at the administrative office. A VP of the library system met with me, apologized, escorted me to the guest computers, and gave me his business card to wave if I was ever bothered again. Taxpayers partially fund those universities, so in my opinion we have paid for limited use of their resources. Every other librarian I’ve interacted with was eager to get me access.

They may be required to ask why you want it, in which case the safe answer is, “I am researching [your topic].” Some universities technically limit access to “researchers,” and this answer gets them off the hook because the term is broadly defined.

I’m not going to discuss local library and open-database searches further, because once you have logged into them, the search is similar to that for university libraries.

How to Find Studies

Name Your Terms

I use Google Scholar first because it is a great way to develop a set of search terms that bring up relevant results. This saves time when you are at the college library. It works pretty much like regular Google. However, the “Advanced Search” option from the menu works more like the university search, and retrieves more specific results.

Think of a few two- to three-word phrases that describe the topic you are interested in, like you would for any Web search. But remember that scientists may use fancier words to describe a concept. It is even more important in database searches than in regular Web searches to try different combinations of synonyms for each word in your phrases. Consider creating “Boolean searches,” too. This is a technique for more specifically combining and filtering out terms.

The rest of these steps may look long and complicated, but that’s only because I include a lot of detail for first-time researchers. Once you’ve used them a couple of times, you won’t need them anymore. Note that these are specific to larger U.S. universities. Smaller public or private schools may provide access, but I’ve never tried them.

Go Back to School

- Use the Web to identify the main library at your nearest public university, as branches may not have guest computers.

- Go to the library and ask at the information desk for “guest access to the research databases.”

Note: They may ask for your ID to record, and give you a code to use for that visit only. Don’t hesitate to ask for help with any of these steps. - Once at the guest computer, plug in a memory stick if desired, and log in if required.

- Open any browser and find the library’s catalog page.

- Go to the “Online Research” page.

Note: The site might use other terms such as “eResearch,” “Magazines and Journals,” “Articles+,” or “Online Resources.” - Click: “Advanced Search” (or a similar term).

Note: This opens a page that allows you to combine search terms and filter results.

Enter Search Phrases

For each of your phrases:

- Enter the phrase, one word per search field, specifying whether to search only in the “Title” or the entire text.

Tip: If you get few relevant results below, or too many irrelevant ones, go back to this page and adjust the search locations. - If the phrases “Peer-reviewed” or “Academic journals” appear somewhere on the page, select that option.

Note: Otherwise one of those should appear with the results list. - Click the “Go” or similar button.

Gather Evidence

For at least the first 20 results:

- Click any title that seems relevant.

- Read the “Abstract” (you may have to click that word somewhere on the page).

- Look for phrases like “results,” “implications for practitioners,” or “advice.”

- Write down relevant information or download the abstract.

Optional: Download Full Article

If you want more details than the abstract provides:

- Click the term “Full Text” wherever it appears on the page, or in Google Scholar, the link to the right of the study title.

Note: A link appears there only if the full article is available. - Download the PDF to a memory stick or e-mail it to yourself.

Later you can review each article as explained under “Follow the Map” in the “Studies Say…” post.

An Example Search

For my recent post on seagull consultants, I first did a Google Scholar search using that and related phrases and found almost nothing except actual seagulls. Then I drove to Davis Library, the main branch at the Univ. of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. At the front desk I asked for “guest access,” and handed over my driver’s license. The librarian pulled out a binder, noted my name and maybe the license number, and after a few seconds on his computer handed me a shard of paper with a short code. No doubt he would have led me to the guest computers, but I knew where they were, a cluster of three on the main floor. I was presented with a log-in window on which I clicked, “Guest Access.” I entered my code number and was informed I had one hour, more than enough time.

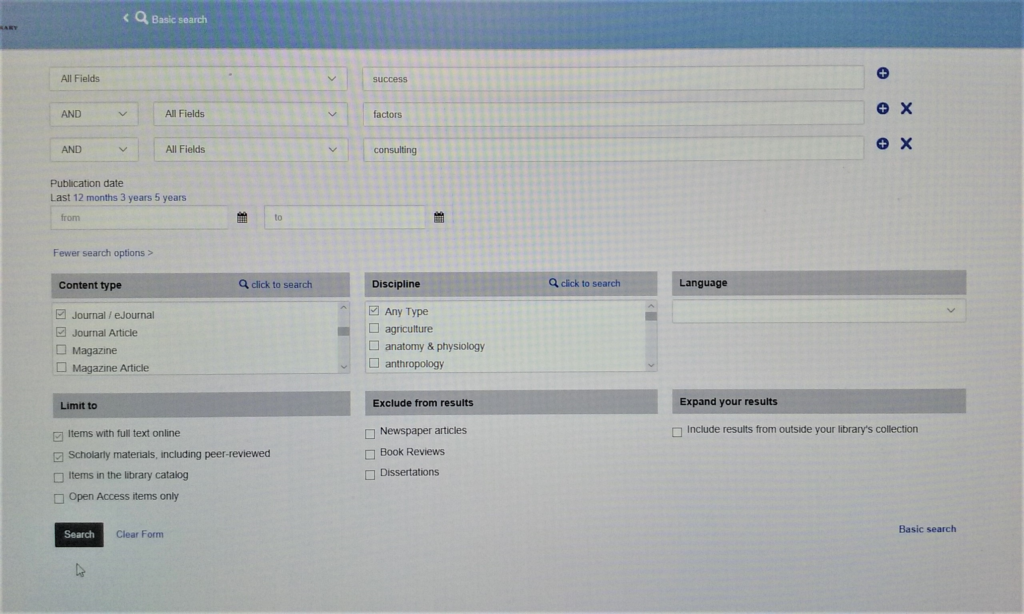

I clicked a browser and it opened to the library’s catalog page. Under “Research Tools” I clicked “Articles+.” On that page I clicked “Advanced Search.” In the first drop-down where it said “All Fields,” I selected “Title.” I entered “seagull.” In the next row, I left “AND” selected, chose “Title” again, and entered “consultant.” I left “Publication Date” open, and under “Content” I made sure “Journal Article” was checked. Under “Limit to,” I clicked two boxes: “Items with full text online,” and, “Scholarly materials, including peer-reviewed.”

Taken together, I was searching for all scholarly journal articles I could download that had both of the words “seagull” and “consultant” in the titles. Nothing exactly like that came up. The closest were two studies on “seagull managers” in the nursing field, which I downloaded just in case. One indeed proved useful.

After several phrases presented few or no relevant studies, it occurred to me to look at general success factors for consulting, in case the amount of client-consultant interaction was covered. I did a “Title” search on “success AND factors AND consulting” to no avail, so tried again with “All Fields.” Bingo. A flood of potential results appeared. Here is the winning search screen, with apologies for the poor quality from a smartphone pic of a computer screen:

If the title in a result seemed right, I downloaded immediately, and with others I skimmed the abstract first. Because the system accesses different databases, the download process varied. With each new one I had to search the page for a link or tab labelled either “PDF” or “Full Text.” Some sites automatically downloaded to a folder on the computer, the location of which I found by clicking the browser’s download icon, while others asked at the bottom of the screen what to do with the file. I moved or saved the file to the memory stick I’d plugged into a USB port on back of the monitor. In the past I have also e-mailed files to myself. Then I sometimes had to close a separate window before clicking my way back to the search results. Occasionally I didn’t notice the database opened in the same window, mistakenly closed it, and had to start again! I ended up with 20-plus studies, 16 of which I read entirely, quoting and citing 6 in addition to other sources.

Go for It

Now it’s your turn. Pick a topic and change your interest in evidence-based management into action. Once you’ve seen the value, I predict you’ll be hooked, and your employees and customers will be better off for it.